- U.S. Customs and Border Protection detected over 42,000 unmanned drone flights near the southern border in fiscal year 2025, a figure that underscores the scale of cartel aerial operations.

- Cartels use drones for surveillance of U.S. agents, coordinating smuggling, and have begun weaponizing them with explosives, posing a direct threat to law enforcement.

- A recent incursion near El Paso, Texas, prompted an unprecedented FAA airspace closure and a military response, highlighting the operational challenge of distinguishing cartel drones from civilian objects.

- Federal agencies face significant legal and jurisdictional hurdles in countering the threat due to restrictive FAA regulations and overlapping authority between multiple departments.

- The surge in drone activity represents a strategic shift for cartels, granting them persistent, sophisticated surveillance capabilities that complicate traditional border security measures.

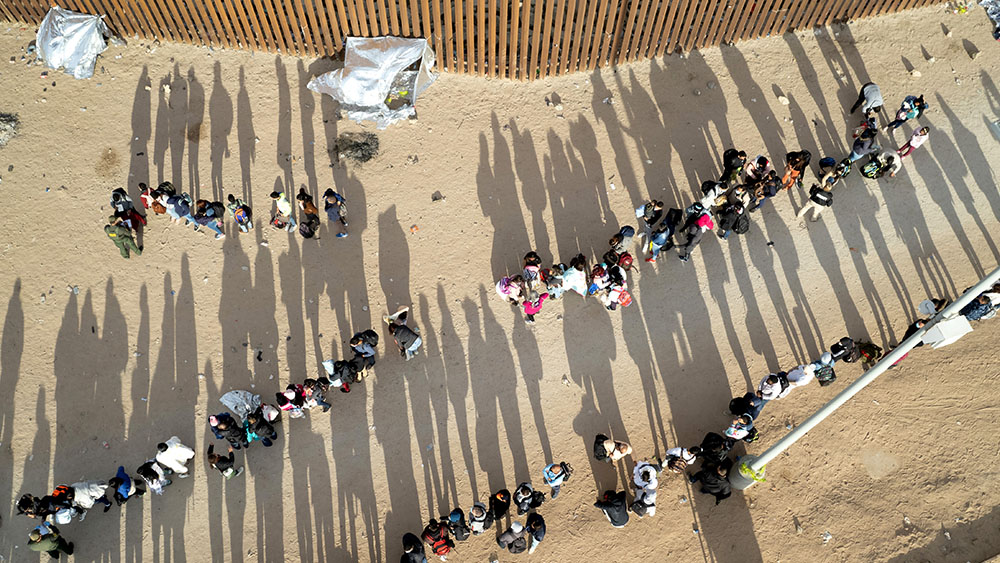

In an unprecedented escalation of border warfare, Mexican drug cartels conducted tens of thousands of unmanned drone flights along the U.S. southern frontier in a single year, leveraging advanced aerial technology to surveil American law enforcement, coordinate smuggling, and probe U.S. airspace. New data from U.S. Customs and Border Protection, revealing over 42,000 detected flights in fiscal year 2025, confirms that cartels have industrialized their drone operations, creating a persistent surveillance network that federal agencies are struggling to counter. This technological arms race, which recently triggered a military response and a temporary shutdown of civilian airspace over El Paso, Texas, marks a dangerous new phase in cross-border criminal activity, challenging decades of security protocols.

An Industrial-Scale Surveillance Operation

The sheer volume of cartel drone activity has stunned security analysts. The CBP’s figure of 42,000 “near-border” flights follows earlier congressional testimony from the Department of Homeland Security citing approximately 60,000 cartel drone launches in just the six-month period from July to December 2024. This averages to more than 300 flights per day, a tempo that indicates a fundamental shift in cartel tactics. Authorities state these unmanned aircraft are not hobbyist gadgets but integral tools for criminal logistics. They are used to monitor Border Patrol movements in real-time, map patrol patterns and response times, identify gaps in physical barriers, guide groups of migrants, and coordinate drug trafficking teams across the border.

From Surveillance to Strikes: The Weaponization Threat

Beyond intelligence gathering, a more sinister evolution is underway: the weaponization of drones. As far back as 2021, cartels in western Mexico were documented modifying commercial drones to carry and drop improvised explosive devices on rivals and Mexican security forces. In October 2025, the arrest of a Gulf Cartel operator in Reynosa, Mexico, yielded a cache of 151 drone-borne explosives, 18 drones, and three advanced anti-drone systems. This progression from surveillance to attack platforms raises grave concerns that such tactics could eventually be deployed against U.S. personnel on the border. The threat has moved from theoretical to operational, forcing a recalculation of the risks faced by agents on the ground.

Bureaucratic Tangles in a High-Tech Fight

Despite the clear and present danger, U.S. agencies report their hands are often tied by a complex web of regulations and overlapping jurisdictions. Federal Aviation Administration rules, designed for civilian airspace safety, heavily restrict where and how counter-drone technologies—such as signal jammers or kinetic interceptors—can be deployed. Furthermore, authority to act against unauthorized drones is split between the Department of Homeland Security, the Department of Defense, and the Department of Justice, creating potential delays in a crisis. This bureaucratic patchwork stands in stark contrast to the agile, adaptive operations of the cartels, who face no such legal constraints on their side of the border.

The El Paso Precedent: A Border Crisis Goes Airborne

The tangible consequences of this drone war reached a new level on February 11, 2026, when the FAA abruptly closed airspace over El Paso International Airport and surrounding areas. The trigger was a suspected incursion by cartel drones, some reportedly approaching sensitive military facilities. The Department of War intervened to “neutralize” the threats, an action later acknowledged to have included downing at least one stray balloon alongside the targeted drones. While the airspace closure caused significant local disruption and was quickly lifted, the incident served as a stark demonstration. It proved cartels could directly impact U.S. civilian infrastructure and that distinguishing their aircraft from benign objects remains a severe challenge, forcing difficult split-second decisions on the use of force.

Cartels as Unconventional Adversaries

The drone surge represents the latest adaptation by cartels that have long operated as hybrid entities—part criminal enterprise, part insurgency, and part corrupt political influence machine. Their evolution mirrors that of non-state actors and terrorist groups worldwide who leverage cheap, commercially available technology to gain asymmetric advantages. The Trump administration’s 2020 designation of several major cartels as Foreign Terrorist Organizations framed them as national security threats, not merely law enforcement problems. Today’s drone fleets operationalize that status, granting cartels a domain awareness once exclusive to nation-states and blurring the lines between crime and warfare on America’s doorstep.

A Contested Frontier

The border landscape has been irrevocably altered. With tens of thousands of flights annually, cartels have established a pervasive aerial intelligence apparatus that undermines physical barriers and patrols. The incident over El Paso confirms that the threat is no longer confined to remote desert crossings but can project into American cities and critical infrastructure. As cartels continue to refine their tactics—potentially incorporating lessons from global conflict zones—the United States faces a pressing need to modernize its legal authorities, unify its defensive response, and deploy technology capable of dominating this new aerial frontier. The data is clear: America’s southern border is now a battlespace in three dimensions, and the high ground is increasingly contested.

Sources for this article include:

Please contact us for more information.